Combines and Concubines (Bonus Story)

It’s important how we define a word and how we use it. Looking at a word or phrase the way we’ve always looked at it isn’t necessarily the same way the Lord wants us to look at it. We need to be absolutely sure our words are used correctly.

Several years ago, my sister took all of us who worked for her travel agency to Little Rock for supper. I was in the front passenger seat while she drove. Three ladies sat in the back.

Conversation part 2 follows.

Don’t look for conversation part 1. There isn’t one. Two reasons: (1) part 1 was not as important as part 2, and (2) I have no memory of part 1.

So picking up in the middle of the conversation, the girl in the middle of the backseat said, “Oh, that’s awful. Yeah, I knew this guy once who was riding his motorcycle through a cornfield, and he ran into a concubine, and it poked his eye out.”

Crickets.

I said, “You mean combine, right? He ran into a combine?”

She replied emphatically, “No! He ran into a concubine, and it poked his eye out!”

I said, “Well, um, in the Bible, a concubine was a kind of second wife. She wasn’t actually a wife, though. Didn’t have the status of a wife. She was more like a servant usually, who was around if the man of the house wanted extramarital dalliances. King Solomon had, like, hundreds of them.”

Crickets.

She asked, “So what’s a combine?”

Children, take heed. Consider this critical warning carefully: stay away from concubines; they’ll poke your eye out.

Y’all Come Go With Us

I’m a child of the 1960s—not old enough to be a hippie but a young child of the ’60s. For that reason, I remember how great the toys were back then. Imagination was a huge predictor of how long those toys would last.

I loved Slinky—not the cheap plastic ones they make now but the heavy ones made out of metal, which made that impressive, well, slinky noise when I held one end in each hand and passed it back and forth for about ten minutes. Then I’d force my little brother to hold one end while I backed up with the other to see how far we could stretch it, eventually pulling it completely out of its intended coil, rendering it useless.

I remember Mr. Machine Robot, a windup mechanical man that, when wound up, marched across the floor, showing all his inner workings through his plastic casing. You could take him apart bolt by cog by nut by wheel and then theoretically put him back together again. Theoretically.

Mr. Machine Robot lived in a bag in the back of my closet for five years because all the king’s horses and all the king’s men—well, you can guess the rest.

Then there was the miracle of Chatty Cathy, my sister’s prized Christmas gift, the wonder doll that spoke three or four classic lines when you pulled the ring attached to the back of her neck. I also remember the big ole can of whoopin’ I got for, with precision, surgically dismembering Miss CC to accurately identify where her voice came from.

Besides those glorious toys, I loved southern words and phrases from the ’60s that have gone out of style or should’ve never been in fashion. Many of them I still use today when an opportunity arises. For instance, the following:

- Southerners don’t say, “You guys.” We say, “Y’all,” or, for five or more people, “All y’all.”

- We don’t say catty-corner. We say cattywampus.

- We don’t say, “Oh wow.” We say, “Good gravy.”

- We don’t have a hissy-fit; we pitch one.

- Southerners won’t tell you, “You’re wasting your time.” We’ll tell you, “You’re barking up the wrong tree.”

- We don’t hand you a Coca-Cola when you ask for a Coke. We ask, “What kind?”

- We’re never “about to” do something. We’re “fixin’ to.” Or we say, “Go fix your plate.”

- We don’t use the toilet. We use the commode.

- We never suppose. We reckon.

- Southerners don’t call people unintelligent. We say they’re “dumber ’n a sack o’ rocks.”

- Southerners don’t check for food in the fridge. We look in the icebox.

- Southerners don’t eat dinner. We eat supper. There’s no such word as dinner. It’s not biblical. We don’t observe the Lord’s Dinner.

- Southerners aren’t “caught off guard.” We’re “caught with our pants down.”

- Southerners don’t pout. We get our “panties in a wad.”

Julia Sugarbaker, on the 1980s sitcom Designing Women, proudly proclaimed, “This is the South. And we’re proud of our crazy people. We don’t hide them up in the attic. We bring them right down in the living room and show them off. No one in the South ever asks if you have crazy people in your family. They just ask what side they’re on.”

A few years back, my brothers and sister and I went to Texas to visit Dad. He was residing in a home for folks living with Alzheimer’s. While there, we drove around Hurst, just around the corner from Fort Worth, and visited some of the old schools, churches, and houses we’d lived in when we were growing up.

On that trip, I thought about all the old southern words and phrases that add such richness to the language I grew up with. We drove by one house, and even the old white screen door looked like the same one from my childhood.

Everything looked familiar, except for one thing. I said, “I don’t remember that big old tree being over on the side of the house like that.”

My older brother, Steve, said, “Tim, we lived here fifty years ago.”

“I know, but it’s so big. I don’t remember it at all.”

“Tim, that was fifty years ago. A half century.”

Even now, that doesn’t compute with me. I guess part of the mystery is that I can still see myself looking out the front window of the kitchen while washing supper dishes. I could barely wait to finish. Only then did I have permission to go around the corner and find all my neighborhood friends to play hide-and-seek. We ran the neighborhood until Mom called us home, which was way after dark and fairly close to bedtime.

Sitting in front of the house that day, I remembered my favorite southern phrase. My dad was a preacher, and usually, on Wednesday nights, after prayer meetin’, we’d go to different congregation members’ homes for fellowship. We kids would have a dessert and drink cherry Kool-Aid while the adults drank hot, thick, aromatic coffee.

The only time I ever got to taste coffee when I was little was on the rare occasion Mom let me climb into her lap at someone else’s kitchen table. She consented to allow me the dunk of my doughnut into her coffee. As a matter of fact, one morning, I woke up while visiting my mother many years later, in my early twenties, and she asked me if I wanted a cup of coffee—a passage-to-manhood moment for me. I took a heart picture that day.

Back in the ’60s, as we prepared to leave the homes of our friends after goodbyes were said, I distinctly remember standing in the dark, just outside the glow of the porch light, and instinctively slamming my mouth shut for fear of kamikaze june bugs. After the small chatter while walking to the car, Dad turned around and said to the hosts, “Y’all come go with us.”

That simple phrase, in my ten-year-old mind, was the perfect tagline to an ideal evening. It said, “We loved being with you, and we wish it didn’t have to end.”

The recipient of this declaration of friendship would reply with something like, “Well, I wish we could. The kids have school tomorrow. We better stay here and get ‘em ready for bed.”

As a kid, I thought it was the best idea ever. The reality never dawned on me the horror that would befall my mother if someone actually said, “Well, all righty then. Honey, go get the kids.”

Even at an early age, I was thankful the Lord allowed me to take what I now call heart pictures: moments framed in my mind and soul, benchmarks of remarkable relationships, and perhaps even profound truth that wouldn’t be realized for decades.

It’s much more acceptable in today’s climate and Christian culture to realize, possibly due to our not understanding when we were younger, that we must rigorously, deliberately seek out and nurture community. The truth is, we were never meant to walk this journey alone.

I don’t think it was an easy task back then. The best my parents could muster to make someone feel important, needed, and valued was a simple declaration of unity, an acknowledgment of friendship that guaranteed “You’re not alone,” without actually having to be vulnerable enough to say it.

“We’re in this together.”

“Y’all come go with us.”

Jesus says in John 15:12–13 (NIV), “My command is this. Love each other as I have loved you. Greater love has no one than this: to lay down one’s life for one’s friends.”

James 5:16–18 (MSG) puts it in a more nuts-and-bolts configuration: “Make this your common practice.” He doesn’t say, “When you have committed a major public sin and need to repent by going forward.” He tells us to make this a common practice: “Confess your sins to each other and pray for each other so that you can live together whole and healed. The prayer of a person living right with God is something powerful to be reckoned with.”

Something powerful.

I sometimes wonder what draws nonbelievers to us or what should bring them to us. In a world that has become freakishly isolated, compartmentalized, and cubicle-like, it’s imperative that they see us love one another and know one another.

Jesus said they would recognize him because of our love for each other, and he said that just after he washed the feet of his disciples.

Just before James’s encouragement to confess sin, he says in chapter 5:7–8, “Friends, wait patiently for the Master’s arrival. You see farmers do this all the time. Waiting for their valuable crops to mature, patiently letting the rain do its slow but sure work. Be patient like that. Stay steady and strong.”

One of my favorite topics of conversation with friends—in fact, my very favorite—is how much I look forward to Jesus’s arrival and what that moment will usher in for those of us who are his. What if we lived out the truth that our redemption is sure and solid? What if we encouraged one another with the accuracy and dependability of that truth, fervently excited?

When I talk about heaven and all the fun we’re going to have and make plans to meet people for supper on a specific day a hundred years from now, trust me, that’s not idle talk. I have a hope that it is real and that God is faithful to live up to his promise.

As time ticks by and I realize this motor of mine will one day stop ticking, the anticipation deepens. I think about all the people who will welcome me when I get there, especially Jesus. I think about my friend Greg Murtha, whom I’ve written about in this book. He’s in heaven now after fighting a courageous battle with cancer.

Thousands of friends and family all over the world covered him in prayer and sacrificed countless acts of service to comfort his family. In one of his last posts on social media, instead of lamenting his circumstance, Greg wrote,

Today will you take your neighbor a muffin or a potted plant? Will you buy that homeless guy a coffee? Will you linger a little longer over breakfast with your family, tell these people you appreciate them or, if you’re bold, that you love them? Make today different while you’re able.

I’ve written about a guy I’m in contact with who’s in prison. He is one of society’s outcasts who need and secretly long for freedom from the bondage of self-loathing, guilt, and shame and who refuse Jesus, not necessarily because they are callous to him but because they think he could never forgive them, much less love them. We all probably know these people imprisoned behind walls of inadequacy, self-condemnation, and selfishness.

I’ve told y’all stories about people I’ve met: a little girl racked with guilt over picking up trinkets in a store without paying for them; inmates, including a redeemed murderer and a grieving mom who lost her boy to suicide; the beautiful radio personality I loved to torment and make laugh on air; dear friends, including one fighting a battle with diabetes and dementia; the faith chaser; the tire changer; and the theatrical mourner. I don’t know where some of these folks are now, but I hope our journey together isn’t over. I pray I’ll meet them again one day. I hope the winding, twisting, bending, anfractuous curves of our lives will crisscross once again. Even if we never physically see each other again on this side of the veil, when we’re all finally home, I imagine standing at the throne, shouting my love to Jesus, and then glancing at someone next to me and exclaiming, “Hey, I know you! I remember you.”

When I hang out with my peeps, it’s a comfortable, mostly unspoken addendum to our journey together that this doesn’t end here. We will enjoy this company, joy, and laughter and look after one another forever.

My prayer is that those living in silent desperation will recognize those eternal moments in our eyes. I pray they will give us the chance to share with them where the surety of our future comes from and how dearly treasured and loved they are.

Jesus is the great adventure.

I pray we will be able to boldly, with certainty, turn to them as we’re leaving and say, “Y’all, come go with us.”

You Can’t Spell Funeral Without FUN

Nowadays, when someone passes away, we gather together and have what we sometimes call a memorial service or going-home celebration. It’s a bittersweet time to remember a life well lived in the service of Jesus. I’ve noticed in the last few years that the gatherings take the tone of the people who are no longer here. If they were Christians, their legacy continues in friends and family, and part of them lives on. It’s a time of heart-swelling pride in knowing their lives are not over and never will be.

That stands in stark juxtaposition to the funerals of my childhood. I grew up in a small church and a Christian college town in a family of singers, and we were asked many times to sing at weddings and funerals, mostly funerals. Because Dad was a preacher for an even smaller country church, we sang for many country funerals.

When most of the kids from college were not in town during summer break, my family spent probably one day a week singing. Funerals back then were not hallowed festivals of rapturous remembrance and tribute. They were dismal, agonizingly morose requiems of lamentation and sobbing. Especially in the country, where nothing significant ever really happens, funerals were the grandest and most pretentious form of entertainment. Funerals were distressing and bleak. It was as though the deceased didn’t just die; they ceased to exist, perhaps because the mourners never had heard what heaven is really like. Paul clearly says in 2 Corinthians 12 that a guy he knew was caught up to the third heaven but was not allowed to say what he saw there, so obviously, some thought, we shouldn’t be dreaming about what heaven is like.

For most people, it seemed heaven was a place we looked forward to only because it meant we were not in hell. I couldn’t imagine heaven being much more thrilling or energizing than endlessly jumping in a bouncy house or eating really good food whenever I wanted it, with the occasional drop-by visit of Jesus when he was making his rounds.

I think that’s the reason funerals in those days were so devastating and even scary. Burials were only mentioned by our parents after they were sure we were intimately acquainted with the idea of death. This practice was clearly designed to be used as a punishment for bad behavior.

When my family sang at weddings, Mom would lean over, poke me, and whisper, “You’re next.” She thought it was cute and funny, until I started doing the same thing to her when we sang at funerals.

I’ll never forget one summer after finishing my freshman year of college. All my college friends from the music department were away from campus for the summer. Some acquaintances in Floyd, Arkansas, asked Dad to preach for a funeral.

Dad asked if I could gather some local choir friends together to sing hymns. Without thinking, I said, “Sure.” I began asking around and discovered the only people available were some friends still in high school. I enlisted them, even though almost every one of the eight was entirely unaccustomed to funerals.

I wasn’t too nervous. After all, we’d all sung out of the same blue songbook our whole lives. I knew they would know the hymns. However, I’d lost my tuning fork a while back, so I borrowed one from my high school choir director. It might be relevant to note I grew up in a church that didn’t use instrumental music for any church function. It was strictly forbidden.

I talked to Dad the day before the funeral and told him who was coming to sing. I strongly informed Dad that these kids were novices at singing at funerals. I wouldn’t put them in a position of being uneasy. I told him he was to tell whoever was in charge that we would sit in the back of the church, far away from the casket. I also informed him we would leave before the final viewing. He said he would make sure the director knew my rules.

On the day of the funeral, I drove around to gather up all eight kids in the family Datsun station wagon.

Our big orange Datsun station wagon had been a gift to my sister, Jacqui, on her sixteenth birthday. Our dad had paid $170 to have it painted orange—really orange. We swore the vo-tech beauty was actually the front half and back half of two different cars soldered together and then spray-painted orange. It was a standard shift station wagon, and the back end had a decal that said, “Fully automatic.” It looked like a dog loping with its hind legs slightly angled to one side as it ran toward you.

Dad gave me directions to the little country church, and we were off. As we turned down the well-traveled road to the church thirty minutes later, I thought it could not have been more picturesque. The small clapboard church with a white steeple rising just above the nearby trees seemed the most serene place I could think of for a funeral service.

Rain, pouring in torrents nonstop for three days before the funeral, had rendered the ground completely soaked. I drove down what used to be a dirt road, which was now slippery from the constant rain. The tiny church sat to my right. Directly across the street, to the left of me, was the cemetery, peaceful, quiet, and pastoral. It seemed a serene and undisturbed location for repose. I parked on the road directly between the church and the cemetery.

Dad was there ahead of us. As I walked to him, the other kids followed behind me, vainly attempting to avoid mud pits. Another gentleman ran out and took my hand. He was the funeral director and would show us where to sit. I glanced over toward Dad but saw him deeply engrossed in conversation with a mourner. As I passed through the front door, I noticed all the flower arrangements lining the back wall of the church instead of surrounding the coffin at the front of the small auditorium. Odd, I thought.

I heard the middle-aged man say to Dad as quietly as possible, “We had to physically pull her out of the coffin at visitation last night.” Dad just grunted and avoided eye contact with me. The gentleman’s comment left me a bit confused but nonetheless intrigued.

I kept walking as the funeral director ushered us down front and into a small, beautifully polished mahogany choir loft directly behind and above the podium, which sat straight behind and above the coffin. Before I could protest, the director scuttled off. I glanced back to see eight impressionable young kids looking down on the closed casket with eyes as big around as their open mouths. I whispered, “Y’all, trust me on this. In three years, you will have sung at so many of these, this will be nothing. I promise.” Not one of them moved or blinked. I’m not sure they breathed. I knew we were in trouble. We sat quietly as guests trickled in.

Finally, it was time to start. The family came in as a unit. The men were staunchly holding up the female family members, exactly as they’d been taught from an early age, and the women all held kerchiefs to their noses, just as it should have been.

Then I heard her—before she ever got inside the small auditorium. From my vantage point, I looked down the center aisle to the back of the church. Into the building she came, held up valiantly by two men: the brother I’d heard talking to Dad earlier and another close in age, obviously siblings. As the brothers all but carried her down the center aisle, I sat almost in awe at the visage before me.

I couldn’t decide if I was more disturbed by the mourning and wailing, which apparently emanated from Dante’s third level of Gehenna, or her funeral attire. She carried the body of Aunt Bea and the voice of Almira Gulch. She wore a pencil-style black vintage dress, which I was sure she’d bought somewhere around forty pounds ago. Appropriate for a funeral, it did cover her shoulders—barely. She wore shiny, pointy-toed black patent-leather shoes, but it was her hat that was spellbinding. It was a pillbox hat with a short veil, but stuck inside the velvet band around the entire circumference were some kind of bird feathers that were not easily identifiable. They were varying colors and lengths, anywhere from a couple of inches to a foot high, not species-specific. I got the feeling she probably renewed the plumage for each occasion. Poor birds! Everyone else seemed determined to ignore the nest perched atop her head. I purposely turned away to keep from staring.

The brothers struggled as best as they could, one on each arm, stumbling as they maneuvered her to the front pew. The entire time, she wailed, “Oh, Daddy! Oh, Daddy!”

The brothers’ futile attempt to console her included words of comfort. “Now, now, Auntie Christa. It’ll be okay. Sit down, and hush now, Auntie Christa.” At some point, I noticed the spiritual implications of her name.

Unfortunately, at that moment, one of the high school kids behind me discovered for the first time what it feels like to experience the embarrassment, guilt, and shame of uncontrollable and inappropriate giggling. At first, I thought she was just coughing. Then I realized she was trying to cover her wheezing snickers.

Fortunately, I saw the funeral dude signaling me to start. I grabbed the borrowed tuning fork out of my coat pocket, struck it against my index finger, listened to the hum of the fork, and gave the kids the pitch for middle C. I began directing the first hymn: “Oh, Lord, my God. When I, in awesome wonder, consider all the worlds thy hands have made.”

Wait. It sounded at least a fourth of an octave lower than it was supposed to be.

“I see the stars. I hear the rolling thunder.”

Even worse, all song directors know the fatal truth that no matter how fast you start a hymn, if you start it too low, it’s going to slow down. After feeling as if I were hiking through molasses, I finally made it to the end of the song.

I was furious and wanted to take it out on someone, so I glared toward the back, where Dad was standing. He averted my scowl and quickly glanced out the open entrance door as if trying to read a tombstone in the cemetery across the street. I looked back at the kids, and they were all looking at me with confusion and maybe condemnation on their faces. One of them actually mouthed, “What are you doing?” And there was still the chuckling girl. Her shoulders were shaking, and she held a tightly clenched fist against her mouth.

Someone mouthed, “Pitch it higher.”

I mouthed back, “I’m using the tuning fork.” It’s right!

Through all this, Auntie Christa was caterwauling, “Why? Why?”

I thought it best to go ahead with the next hymn. I pitched it in the correct key with the tuning fork and began. Somehow, it became an awkward duet with Auntie Christa. She would not be outdone.

“Low in the grave, he lay, Jesus, our Savior. Waiting the coming day, Jesus our Lord—”

“Oh, Daddy!”

“Up from the grave—”

“If I could hear him preach just one more sermon!”

“He arose!”

The song of celebration, still pitched embarrassingly low, became a funeral dirge, somehow oddly appropriate but not what I originally had envisioned. When it was over, I refused to even look back at the kids. I knew what they were thinking. It wasn’t until I returned the offensive fork to my choir director later that I noticed I had been given a G tuning fork instead of a C fork. I was, in fact, starting every song a half octave too low.

After we finished singing, Dad took his turn. He walked to the front, deliberately averting my deeply furrowed brow, and stood at the pulpit, between us and the coffin. He gave a heartfelt message about death, which he was forced to scream, trying to be heard over the rivaling howling from Auntie Christa. The family no longer attempted to quiet her. A few kids close by her bent over, gathering up occasional tufts of bird fuzz that flew off her head.

Finally, it was done. I felt sure the funeral dude would escort us out before the final family viewing, but he did not. I sat in horror as he and his minion helper marched—and I do mean marched—to the front and opened the coffin.

There we were, looking straight down into the embalmed face of a ninety-something-year-old Baptist preacher, who, I’m sure, to the kids, looked astonishingly like the Crypt Keeper.

There was an audible gasp in unison. I turned around and witnessed eight sixteen-year-old kids metamorphose from well-adjusted high schoolers into clinical case studies.

A couple of them averted their gaze downward to the floor, but the others looked as though they were half expecting and hoping that Daddy would jump up and say, “Just kidding.” Meanwhile, Auntie Christa was proclaiming to the entire congregation that she no longer wanted to live. At that moment, I was close to making her wish a reality.

I looked back and said, “Let’s go,” leading the procession of eager followers down the front aisle before the guests and family could parade past the open coffin. I felt compelled to get them out of there as fast as possible before they were forever mentally scarred. I would deal with Dad later. We passed him. I purposely avoided eye contact with him. He tugged my coat sleeve and whispered, “Um, the funeral director was wondering if the kids could carry the flowers to the grave site across the street before the family walks over.”

I whispered back, “Dad, I believe you have successfully turned eight bright, well-adjusted high school students into Children of the Corn. We’re going to do this one last thing, and then we’re out of here.”

At my direction, each kid grabbed a container of flowers, and we headed across the soggy, muddy street into the cemetery. The chuckling girl commented on the lovely white stones lining the walkway. I informed her that they were actually grave markers, and I walked ahead. Suddenly, I heard someone whisper, “Excuse me. I’m so sorry. Excuse me.” I watched as chuckling girl passed me, apologized to each grave, and then long-jumped across them, precariously balancing her vase of flowers in her arms.

Something inside me snapped. I set my flowers down and laughed. In fact, I laughed so hard I leaned across a tall tombstone and continued with my own inappropriate guffawing.

Then I heard an excruciatingly loud whisper, “Tim. Tim!” I glanced up, wiping tears from my eyes, and observed Dad leading the procession of mourners across the street from the church toward us. All of them were looking at me with utmost disdain.

Suddenly, a haloed dome of feathers poked out from somewhere in the middle of the group, apparently to see what the holdup was. Auntie Christa, chagrined that someone else might be stealing her attention, abruptly howled and flailed her arms. She ran toward the open grave and deliberately fell just short of it, hitting the dry plastic grass in a dramatic dead faint.

Her road-weary brothers, obviously exhausted from the emotional and physical toll, just stood there. Everyone stared at her. When it was apparent no one was going to rescue her, Auntie Christa slowly raised her bird head and looked around. Broken and bent pinions and the few plumes left on her head wafted in the breeze. She looked less like a phoenix rising from the ashes and more like a deranged, run-over peacock. As her brothers wearily began the four-hundred-mile journey to pick her up, I looked at the huddled kids and jerked my head toward the car.

This time, as I passed Dad, we both avoided eye contact. I all but ran to the car, jumped in, and started the engine as the kids piled in. I threw the car in reverse and heard the dreaded spinning of wheels against mud. There was a definite groan from all the passengers in the car as I tried several times to put the car in drive, reverse, drive, and reverse. Nothing. So three of my guys jumped out and bounced the orange station wagon.

Someone yelled, “Gun it!” so I did. The car was removed from the deadly clutches of the offending mud, and everyone let out a tired cheer. I looked in the rearview mirror and saw my three guys covered from head to toe in slimy red Arkansas mud. One wiped it out of his ears, one wiped it out of his eyes, and the other just stood there. I was sad he didn’t finish the tableau.

I glanced over and watched in fascination as the entire funeral company giggled along with all of us in the car, except, of course, Auntie Christa, who leaned morosely against her brother.

We drove off into the cloudy day.

In the years following

Power

As I’ve said, before the beginning of January, I always choose my word for the year. This year, I chose power. I never get a clear idea of how impactful and far-reaching the word I choose will prove to be. I’m always surprised how the Lord broadens my vision of him, the world around me, and even my own personal study of his Word.

This year, I wrote down on note cards Bible verses specifically using the word power. On the headboard of my bed, I have Colossians 1:11 (RSV): “May you be strengthened with all power, according to his glorious might, for all endurance and patience with joy.” I’ve found this verse particularly significant while enduring many of the events happening in the world right now, including having to endure masks; watching the dark abyss called politics; and having to say, “See ya later,” to my precious pup Chester. I feel as if 2021 is saying to 2020, “Hold my beer.”

The wardrobe in my bedroom has 2 Peter 1:3 (RSV) taped to it: “His divine power has granted to us all things that pertain to life and godliness through the knowledge of him who called us to his own glory and excellence.” Knowing this helps me remember that he has the power to help me navigate these perilous times and find peace in the midst of the turmoil. I have verses taped to the microwave, the bathroom mirror, and the front door of my house. I even have one on the top left corner of my television screen: 1 Corinthians 4:20 (RSV), which says, “For the kingdom of God does not consist in talk but in power.” The verse on my bathroom door reads, “Therefore I tell you, whatever you ask in prayer, believe that you have received it, and it will be yours” (Mark 11:24 NIV). That verse doesn’t specifically use the word power, but I wrote these verses the day the Powerball was close to a billion dollars, and frankly, after hearing the announcement of a winner, I had a hard time feeling the accuracy of that particular verse.

One of my favorites hangs on my bedroom door: Revelation 5:13 (NIV), which says, “Then I heard every creature in heaven and on earth and under the earth and on the sea, and all that is in them, saying, ‘To him who sits on the throne and to the Lamb, be praise and honor and glory and power forever and ever!’” This verse became a safe harbor during January.

Mom left for heaven on Wednesday, January 13, 2021. The previous Saturday, she enthusiastically fussed at her TV, completely wrapped up in a Razorbacks game with my brother-in-law, Jim. On Sunday, she was not feeling well, so her caregivers decided to move her into a hospice environment and attempt to regulate her meds. On Monday, Ginger called, telling me I needed to get there as soon as possible. I packed up right then and headed to Fayetteville.

We all knew Mom had been living on borrowed time for a few years. We knew congestive heart failure continued to sap her energy and ravage her body more and more. But she always rallied when surrounded by her kids and grandkids.

I’d spent a few days with her just a couple of weeks earlier, during the Christmas holiday. She was alert and thrilled every day I walked through the little apartment my sister, Jacqui, and bonus sister, Ginger, painstakingly decorated for her.

Relaxing in her recliner, which most times doubled as a throne, Queen Eunice watched the Game Show Network or browsed through the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette on her iPad. Word puzzles and fill-in-the-blank Bible studies littered a little table comfortably within arm’s reach beside her.

She would light up in a radiant burst of life when any of her kids or grandkids walked through the door. Leaning forward and taking our face in her hands, Mom assured us of how much we were loved. Her pride in her family never went unvoiced. We never left her side without knowing how important and valuable we are.

To the right of her recliner, on a little side stand, sat a digital picture frame, a Christmas gift from my brother a few years earlier. She motioned us down onto the love seat next to her, and together we watched picture after picture scroll through the frame. All her kids knew the email address for the frame. We imagined her unbridled excitement when she discovered the treasure of a new picture or two added to her priceless collection.

On the small kitchen table behind her sat a large red bowl filled with candy. It was mandatory, almost a religious rite, that we leave her cozy abode with a handful of bite-sized goodness. Even the day she left her apartment for the last time, the guys wheeling her out on a stretcher were required to stop and fill their pockets.

Only two people were allowed in the hospice room at a time. Jim whispered his love to Mom, switched places with me, and went to his car to wait. Jacqui and I sat on either side of Mom’s bed, each of us holding one of her hands in ours. We stroked her face and arms as she slept and labored to breathe. We quietly declared our love for her and promised we would all look after one another. We prayed and asked Jesus to welcome her home. We encouraged her, reminding her of all the precious friends and family she would be hugging soon and the applause, whoops, and shouts of excitement and welcome she would hear as her own personal angel carried her to the shores of heaven.

Jesus, standing there to meet her, grabbing her up in his arms, with a twinkle in his sparkling eyes, would say, “I’ve been waiting for you. I’m so happy to see you. You did such a good job. Welcome home.”

Mom took her last breath.

We sat silently for a few seconds as we sensed the electric power of the Holy Spirit envelop the small room. Jacqui and I reached across Mom and grabbed each other’s hand. Tears flowed freely as Jacqui calmly pressed the call button. We waited for the nurse to come in, place her stethoscope against Mom’s chest, and listen for a pulse. I watched quietly and was finally able to say, “Is it over?” The nurse nodded and told us she was sorry for our loss.

Jacqui and I stood at the end of the bed, holding each other tightly, waiting for the nurses to come prepare Mom to be moved to the funeral home in Searcy. I looked at Jacqui and said, “I don’t know how people who don’t have the hope we have survive this.”

At Mom’s visitation, friends we’d known all our lives, school buddies, Mom’s coworkers, college teachers and classmates, and even several of my precious friends from church and Creative Living Connections class came to support me and my family. If you ever have wondered if taking a few minutes to be with someone makes a difference, trust me, it does. John and Pat Knott showed up. I determined before I arrived at the funeral home that I had cried enough and wouldn’t need to during the visitation, until I looked up and saw them walking down the aisle. Then Randy and Janet Granderson and David and Cheryl Richards came in. I started up again.

My most vivid memory of the day is talking to David. He said, “If you want to see what your mom’s legacy looks like, look around.” I did. The room was not a room of sadness, mourning, or grief. People were hugging, laughing, telling stories about Mom, and catching up with each other. Each person there, each relationship, connected through the love and care Mom’s unique personality had exuded. The atmosphere emanated exactly the warmth and joy Mom always had hoped everyone around her would feel during her journey on earth. It was comfortable. It was healthy. The friends and family gathered that day experienced a bit of the lightheartedness, comfort, and frivolity of heaven. Thankfully, my childhood buddy Sherry Barnett Hunter stood right beside me for more than an hour, reminding me of the names of people I couldn’t remember or flat-out didn’t recognize.

As I looked around, I was reminded of a quote from C. S. Lewis’s final book in the Chronicles of Narnia, The Last Battle:

The things that began to happen after that were so great and beautiful that I cannot write them. And for us this is the end of all the stories, and we can most truly say that they all lived happily ever after. But for them it was only the beginning of the real story. All their life in this world and all their adventures in Narnia had only been the cover and the title page: now at least they were beginning Chapter One of the Great Story which no one on earth has read: which goes on for ever: in which every chapter is better than the one before.

We followed Mom’s body to a tiny cemetery in Romance, Arkansas, where she would be buried close to Ginger’s mom and dad on one side and a tiny country Church of Christ on the other, which I’m sure gave her great satisfaction.

Another great friend of more than forty years, Doug Langston, brilliantly officiated the service. It was perfect. He is close to each of us siblings and offered tender insight on how Mom had influenced us and the world around us. His precious wife, Paula, was with him. Paula is another childhood friend. I attended church with her when we lived in Shreveport during our junior high years, before she and Doug met. I love how the Lord brings relationships full circle.

I would also like to add that as a gift to Doug, the family bought a gift card to one of Doug’s favorite hangouts in Searcy: Wild Sweet Williams Bakery. Seriously, they have some of the best pastries on the planet. I bought the card for him. It was for $102.37. I thanked him in the card by saying, “I bought the gift card for you. Then I decided I really needed a cinnamon babka.”

A couple of weeks ago, we kids were trying to decide what we thought Mom would want etched on her tombstone. One of my suggestions would have been “Dear Jesus, do not let her make meat loaf.” Mom was a great old-school southern cook, except when it came to meat loaf. It was wretched. I decided it wasn’t worth mentioning. Jim said he found out we could do a video hologram about basketball with a laser beam switch for $20,000.

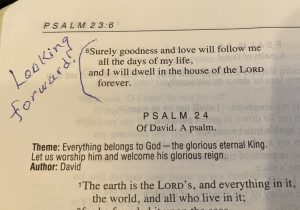

After further discussion, we knew she would love a verse from the Bible, so we threw out a few ideas: “I have fought the good fight, I have finished the race, I have kept the faith” (2 Timothy 4:7 NIV), “In your presence there is fullness of joy; at your right hand are pleasures forever more,” (Psalm 16:11 ESV), and “No eye has seen, nor ear heard, nor the heart of man imagined, what God has prepared for those who love Him” (1 Corinthians 2:9 ESV). I recommended the end verses of Psalm 23 (ESV): “Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me all the days of my life, and I shall dwell in the house of the Lord forever.” I offered that if it was too long a passage, even the last part, “I will dwell in the house of the Lord forever,” might be appropriate.

After finding out that we could get whatever we wanted etched, we decided those verses would be the best. We knew Mom would love it.

Jacqui kept Mom’s Bible. Those sweet, ancient pages, worn with years of reading, studying, and memorizing, had cherished verses circled. A couple of days ago, Jacqui was browsing through and sent me a picture from Mom’s Bible:

My last power verse is the following: “May the God of hope fill you with all joy and peace as you trust in him, so that you may overflow with hope by the power of the Holy Spirit” (Romans 15:13 NIV).

Trust and Obey

Bob Perkins and I have been friends for more than forty years. We were in college theater productions and were Chi Sigma Alpha brothers. I was his pledge master. He swallowed a lot of raw eggs—rough night. I love Bob. I love his heart.

Sweet Tim,

How’s my own favorite angel?

So not to lay too much need on you. But I’ve been thinking about folks who believe that God is in control. Then I ask them to help me understand what that means for them. Definitely not asking folks to defend or justify that belief. Just asking different people what that means for them. I’m someone who would love certainty but doesn’t really expect it. And who, on my best days, is content with and intrigued by mystery.

So even if “God is in control” is really more of a prayer than a certainty for someone, that’s worth knowing to me. But if it means something more definite, perhaps if it’s based on some experience or even revelation, that would be worth knowing too.

This is a super long way of asking: When you have time, would you mind telling me what it means to you to say God’s in control? I don’t know that I can say that. Surprise. Why else would I be asking?

I guess I can try my best to align my faith with Dr. King’s and Gandhi’s assertion that the long arc bends toward justice. And I’m pretty sure I believe that “in the end, there is love.” Though I wonder if I could hang on to that if it was really tested for me.

I don’t like what feels to me like my weak faith; possibly as much because I struggle with wanting stronger faith but not really being disciplined enough to do the things that I expect would help strengthen it: much more prayer, meditation, letting go of things that make me feel unworthy or unholy, etc., etc.

I’m scared enough by the state of the world that I have turned into a not very good sleeper anyway; it’s very common for me to wake up at 4:00 a.m. and not be able to get back to sleep. Which would be okay if I didn’t have to work regular hours and be available to my family.

Do people of deep faith and attachment to God, like, oh, say, you, usually sleep well? Maybe strong people feel more or less like I do and just move ahead anyway.

Anyway, I’m starting to ramble. I just wanted to ask you that question. No need for a quick reply if you want to take time to think about it. Man, oh man, do I love knowing you.

I wrote back,

Earlier this week, I read your post about your dad leaving this life, and when you said other people have a clearer idea about what’s next than you, I shed more than a few tears. Mostly because I can’t bear the idea that someone I dearly love wouldn’t know, dream, and have visions of what our future home will be. I know I prayed at that moment that you would have that absolute faith that would help you sleep better.

And by the way, no, having faith doesn’t always assure one of eight straight hours of peaceful slumber. I wish I could hug you right now. But know this. I prayed last week that you would have a clearer understanding of faith. Today you asked. It’s interesting, and not coincidence, I’m positive, that you would ask that question now.

November of 2006, the week before Thanksgiving, my body went crazy and began to shut down. I felt like I was getting the flu and went to bed, feeling very sluggish and feverish. For the next twenty-four hours, I ran to the bathroom every hour or so with severe diarrhea. TMI, I know. But hang with me. Then my bowels completely stopped. Within hours, my bladder completely stopped functioning. Then fatigue set in to the point I couldn’t function at all.

I was scared.

I was sent to a cornucopia of doctors over several months for MRIs, CT scans, spinal taps, and x-rays. I visited urologists, internal medicine doctors, a gastroenterologist, and, finally, a neurologist. Five months of uncertainty and fear. My neurologist finally diagnosed a disorder called transverse myelitis (TM). It’s a first cousin to multiple sclerosis (MS). The recipient of this disorder experiences the same symptoms as MS. As a general rule, though, those symptoms don’t progress like MS. And depending on where the virus strikes across the spinal column is how severe the symptoms are. Everything below the strike zone is affected.

Very few professionals really know about TM, because only one in eight cases out of a million is diagnosed with it. During the five months of not knowing what was wrong, I leaned heavily on my extensive experience with paranoia. Every exotic disease known to mankind would soon result in my inevitable demise.

During that confusing, challenging period, I never questioned, “Why?” I never got mad at God. I never doubted his love, sovereignty, or grace. I didn’t ask, “Why me?” I know that earlier in my life, I may have wondered. But during this time, I said out loud, “Okay, Lord, how do I use this to show your glory?”

I finally gave myself permission to grieve. One afternoon, I sat on my deck and cried. And when I say cried, I mean ugly sobbed. Snotty-nosed, pillow-over-the-face, wet-T-shirt-contest (and not in a good way), gut-wrenching, powerhouse, blubbering-mess sobbing.

Then I stood up, took a step, and moved forward. I had to figure out what a new normal was going to look like for me.

It’s not now, nor will it ever be, easy. It’s called an invisible disability for a reason. I don’t talk about it often. Most people are unaware that I deal with it. Chronic fatigue is the worst symptom. I will always be tired, and I never know when a severe case will hit. Some days I can barely get out of bed. I will never do many things that used to bring me joy.

I don’t have much of a bucket list anymore. But then again, I don’t really need one. The joys of heaven will make any wish here seem less than a shadow. I don’t think the Lord will use me to part a sea and save a rogue nation from approaching enemies. I won’t run a marathon, although I’m considering a half marathon someday—maybe. I doubt I’ll teach in a packed stadium where thousands will give their lives to the Lord. To many in the world, I suppose my life might even look like a failure. Because they don’t know.

I don’t necessarily see myself as a man of great faith. I’m not even sure what that means. I do have faith. I do my best to be faithful. And I recognize that even the faith I do have comes from God. I regularly ask for more.

Over the past years, I have learned a few lessons. But those lessons, as is often the case with most people, have been gleaned through fire. Allowing myself to be refined by it. Depending on an ever-deepening relationship with Jesus to keep my spirits, occasionally sinking in a sea of despair, buoyed in his ocean of mercy and grace.

I know that I trust him. I know for certain that he is working all things for my good. But believing that truth doesn’t necessarily mean the experience is pleasant.

Look at Abraham.

Abraham, seventy-five years old at the time, whose name in Hebrew means “Father of many nations,” heard clearly God’s promise that he and his sixty-five-year-old wife, Sarah, would have a child. Twenty-five years later, Isaac was born. Promise fulfilled finally.

But then God threw a wrench into the plan and told Abraham to offer Isaac as a sacrifice. I have read this story a hundred times and heard it from the pulpit as many. I always thought Abraham, this great man of faith, merely took Isaac, who carried the wood for his own execution, up a hill behind their house, and, once there, with knife-wielding hand hovering over Isaac’s prostrate body, felt the hand of an angel grab his arm and save the day.

That’s not what happened at all. Well, not emotionally anyway.

Abraham knew God’s voice. He’d heard it many times before. So he knew the command was from a friend, not an enemy. He had to obey. God told Abraham to take his “only son” (the promised one) from their home in Beer-Sheba to Mt. Moriah and there kill him and burn him as a sacrifice to God. Far from a quick two-hour jaunt up a hill behind their home, Mt. Moriah loomed in the distance, three days away.

Three days.

Walking beside his son for at least seventy-two hours, Abraham found himself on a journey he couldn’t possibly understand. He had plenty of time to process. God had promised he would have a son. Abraham had waited a quarter of a century for that promise to come true. And now, many years later, he was asked to not only see his dream of becoming the father of a great nation die, but a knife in his own hand would be the thrust that ended it.

Abraham sat in confusion beside a campfire for two nights, watching the deep, steady breathing of his sleeping heir. According to God’s commitment to Abraham, Isaac’s legacy would include being the first star of billions. And Isaac slept in perfect confidence, knowing his father kept watch over him and would protect him from harm. How Abraham must have grieved. Silent tears for what was to come.

Anger. He’d waited decades for Isaac. And he’d already lost one son.

Confusion. What was God doing? Where was the plan?

Bitterness and resentment. God shouldn’t have led him on without revealing the outcome.

He was old. Would he live to see God’s promise fulfilled another way?

How could God cut Isaac’s life short when there’d been so much hope?

Would God miraculously raise Isaac from the dead?

This seemed an exceedingly unfair, harsh, grim way for Abraham to prove devotion.

Even if God had a different plan, Isaac was Abraham’s beloved son. How could Abraham survive the loss, the absence of this gift he’d prayed for, waited a hundred years for, raised, invested in, and unconditionally loved from birth? How could he reconcile the faithfulness he’d experienced from God with his anger and resentment focused toward this same God, who now commanded him to kill his child? The God he’d raised Isaac to obey, worship, love, and trust.

Abraham’s heart battled for equilibrium between the assurance of God’s faithfulness to his promise and the desolate, bleak inevitability that lay a few miles ahead. Afraid to sleep, through tear-glazed eyes, he scrutinized embers as they swirled and floated upward and away from a dying fire. Maybe he prayed God would speak to him from the flames, as he had spoken to Moses from a burning bush. As the cold black of a starless night enveloped him, he felt the creeping chill of loneliness surround him. Abraham’s prayer went unanswered.

Somehow, we’ve missed—or forgotten—the concept that biblical characters were just as human as the rest of us. We want to believe we understand the complete trust that those faithful figures exhibited. The confidence in God we long to emulate. We read stories in the Bible of God’s people doing outrageous things for him. Something that often, he specifically commanded them to do. Yet sometimes we believe we’ve failed spiritually if we experience adverse or weak emotions in the midst of the fire.

You see, I spent way too much time in my life trying to be happy and comfortable. And the reality is that I was never made to be 100 percent comfortable here, only reasonably happy. I don’t really belong here. I believe the Lord has left a space in my heart, a longing—a hankering—for something I’ll never find here on earth. It will be realized only when I see him face-to-face. Then, and only then, will I be totally fulfilled. The Lord never called me to seek total happiness in this life. He has called me to be obedient. And like you, I think I have in the past fought valiantly to stay in control. Do it all my way.

But I have learned that surrender to Jesus is my safe place.

My health will never again be in my control. It never really was. Jesus is the one place I can go for assurance that I’m loved despite my weaknesses, disappointments, failures, and anger. And there alone is where I ultimately find absolute peace. There will always be issues I have to give up to him.

But the point is that these things always turn my gaze back to him. It rereminds me to remain, as much as humanly possible, in a state of brokenness and surrender if I really desire to be healed and whole. I’ve learned that suffering isn’t ennobling; a relationship with Jesus is.

So now it is almost out of a sense of adventure that I embrace those moments when the Lord reveals previously uncharted areas of my heart where I need to give him jurisdiction. I have learned that every moment of every day, I’m creating my own history. And the choices I make today will be a great predictor of my future. If I can, in the moment, remember that, it will make a vast difference in how I respond to any given situation.

I can choose to respond with a Christ-regenerated character, or I can revert to old knee-jerk defensive posturing that got me to the position I was in many years ago: a lonely, desperately precarious, and discouraging season, pleading with doctors and God for a diagnosis, filled with uncertainty, hurt, resentment, confusion, and fear.

I don’t know about tomorrow. But today I choose dependence. Whatever happens, I choose to allow it to turn my eyes toward Jesus. And I courageously make the choice to continue my adventure with him. Ten years from today, I want to look back at this historic moment and know that I chose the security of wiser actions, love instead of judgment, and acceptance instead of condemnation of others or myself.

I choose dependence. I accept relationship instead of feeble, worn-out patterns that led to frustration and powerlessness at best.

So that’s about it for now. I don’t know if this will help you, my good, well-loved friend. I think I just needed to process for a bit, and you were there at the perfect moment. You need to know that it wasn’t a mistake. Thank you for being there for me.

Bob, I pray and will continue to pray you find what I’ve found: an unfathomable and mysterious grace that willingly sustains us forever through love and acceptance.

I hope you’ll experience, as I have, how God is in the resurrection business, even for dreams that have died. The infinite possibilities available with Jesus. I pray you’ll find the humor and wisdom that a life lived in real community with him and others can offer. I pray you learn the savage beauty of forgiving and being forgiven, especially by yourself. That you will courageously risk sifting through every heartache and victory, as sloppy, broken, and precious as the process can be.

To finally find the way to show God’s glory.

I pray you will be delivered from chains of the fear of letting go and allowing God to be in control. It’s safe there. I pray you would be freed from the prison of isolation and the dark, dreary dread of an uncertain future into the arms of a ridiculously wild, fiercely passionate, and outrageously unrestrained love affair with Jesus Christ.

I pray you will find what I have discovered: hope!

At what point can we identify the faith character of Abraham during the turmoil? In one sentence.

As they climbed Mt. Moriah toward the site where Isaac was to be sacrificed, Isaac reminded his father that they had flint and wood. And then he innocently asked Abraham where the sheep was for the burnt offering.

With one of the most heartbreaking responses in all of scripture, and filled with the horror of this truth, Abraham told Isaac, “God himself will provide the lamb for the burnt offering, my son.” The declaration was valid enough. But I believe the entirety of Abraham’s wounded heart was wrapped up in those final two words: my son. The hope. The promise. My child.

Abraham trusted God. The only altar on which Abraham could pour out his anguish was his belief that God was true to his nature. God had always been faithful. And it would be impossible for him to be anything other than constant and consistent.

The truth of God’s nature was more reliable than Abraham’s situation. Knowing and believing that essential fact legitimized Abraham’s final act of faith.

Climbing Mt. Moriah, which in Hebrew means “Seen by Yahweh,” Abraham chose obedience above emotion. He chose obedience over what he could see. He chose obedience instead of disbelief. In the face of the impossible, Abraham chose to believe. And he chose to obey.

It’s all about being obedient. There have been scant few times in my life when I’ve had a clear picture of what was around the next bend. The next curve. The anfractuous nature of life always seems to catch me by surprise. I never know what God is doing. What he is up to. There’s no security there. I’ve found the only protection in this life is resting in who he is. And I rest knowing he is for me.

I believe in his promises. I know he’s done what he promised. He’s my God. And he provided the Lamb. So I choose obedience.

My prayer for you, my good brother, is that God will give you enough peace to accept his promises, his perfect plan for you. Mostly, I pray the great Star Breather will lead you to an ever-growing understanding of his peace and security. Your only responsibility? Trust and obey.

When God gave Abraham the promise of Isaac many years earlier, Abraham believed. He was obedient.

And the Lord counted it to Abraham as righteousness.

The Trombone Player Wore a Bouffant

Sometime in the summer of 1972—I’m reasonably sure it was mid-August—I remember it being blistering hot. Sweltering, eggs-frying-on-a-sidewalk hot. I was leaving junior high and heading to sophomore status at Searcy High School, a period of life when everything was changing: school, body, and definitely attitude. Everything in life was abhorrent, hilarious, loathsome, fun, and rebellious. Friends were the ultimate expression of loyalty and cutthroat exploits. Friends were the center of the known universe. Parents knew nothing and could do nothing right. I didn’t honestly think they were ignorant; they just thought they knew everything (anything).

One particular Saturday, I was just finishing summer band rehearsal at the practice field, which was just behind Ahlf Junior High. Mom informed me as I threw my trombone into the back and jumped into the front seat beside her that it was way past time for a haircut. No big deal. She would drive me to Hickmon’s Barber Shop on Race Street, a little ramshackle wooden shop, as I recall it, with maybe only two chairs. I can’t remember anyone ever working there besides Mr. Hickmon. One seat sat empty every time I was there.

At any rate, we were not going anywhere near Race Street. In fact, we barely went the length of a football field before turning into a house adjacent to the stadium. I immediately recognized the sign out front: Merlene’s Beauty Shop.

Merlene Barker was Mom’s dear friend from church and the manufacturer of most every woman in town’s coif. For some reason, she apparently never had recovered from the death of John F. Kennedy, because most every woman coming out of her salon was channeling the exact same flip Jackie had a full decade before. Except for my mother, who insisted that much like the basic black dress, the beehive would never go out of style. She usually said that at bedtime while wrapping her head in toilet paper.

For some undefinable reason, as with a rabbit when it senses danger—a coyote or woolly mammoth—every ligament and tendon in my body tightened into defensive mode. “What are we doing at Merlene’s?” Somehow, I knew we weren’t there to pick up one of Merlene’s amazing casseroles, the culinary marvels she was famous for making when there was sickness or a death in the family. “Why aren’t we going to Hickmon’s? And where’s Andy?” My little brother was almost always in the mix when it was haircut time.

“Hickmon’s is closed today for some reason.”

I can’t remember if Mr. Hickmon was sick that day or out hunting with his boys, but I’ve never entirely gotten over the resentment of what transpired over the next hour.

Mom tried to sound excited. “Andy was finished, so I dropped him off at J. R.’s while I ran some errands.” J. R. Betts was another friend of the family. She’d dropped my little brother off at J. R.’s gas station while she came to get me. “Merlene wasn’t busy today, and she said she would be happy to do your hair.”

Do my hair? My breath caught in my chest as I remembered the time Merlene had given my little sister a perm and burned her hair off at the crown. To this day, Jacqui still calls her “Mom’s old-lady hairdresser.”

“Mom, I can wait till next weekend. It won’t get that much longer.”

“I’ve already paid her, so get in there.”

Many people, when they are in an unnatural, albeit nonfatal, accident, will experience flashbacks. They recall small bits and pieces, pictures of the event, and not the entirety of the cataclysmic, life-shifting episode. As I walked into the room, my first thought was to wonder why my mother didn’t whisper, “Dead man walking,” as I shuffled to the chair in the middle of the room.

Merlene was thrilled to see me and exclaimed how excited she was since she rarely ever got to work on boys.

I couldn’t compartmentalize any of the smells in the place: a mixture of bleaches, dyes, and—what? Burned hair? Merlene began her ritualistic persecution by strangling me with a pink-and-blue-striped plastic apron thing. Before I could instinctively rip it off, the chair was jerked back into waterboard position. I have to admit, the hair washing wasn’t half bad. I think I fell asleep, until the chair was unceremoniously thrust back into an upright position, and Merlene began circling me with a pair of scissors and a comb.

No clippers?

Merlene absentmindedly conversed with Mom while she snipped at my head. They talked about church and what someone had worn to someone’s funeral. They laughed and giggled, which was annoying to me—stupid stuff.

Then Merlene began performing some kind of sardonic treatment to my head, as though she were raking it with a fork, as if she were combing it backward or something. I asked, “Are you teasing my hair?”

She joked, obviously for the hundred thousandth time, “Oh no, honey. If I were teasing your hair, I would be doing this.” She pointed her fingers at my head and said, “Nyea, nyea, nyea, nyea, nyea nyea.”

I assumed at least one person over the past several decades had found that hilarious. I, however, did not.

I rolled my eyes as she continued to tease my hair. The entire time she was teasing, she was spraying me with some kind of lethal toxin. My eyes were burning with the fires of a thousand volcanoes, and I was unable to take in air, gagging as I gasped for what I felt sure were my final two or three tattered breaths.

Just before I went unconscious, I had two thoughts almost simultaneously. The first was This is what females go through weekly, and they rarely come out of it genetically altered, as if they grew up next to a nuclear power plant China syndrome meltdown disaster. The second thought, as I glared at my mother, who was mysteriously absorbed in a Southern Living magazine, was For the love of all that is holy, I am your son. Why aren’t you doing something to save me?

Finally, it was over. Merlene stood back, crossed her fleshy arms, cocked her head to the side, and exclaimed, “Oh!”

Mom lowered her magazine, looked up for the first time, and furtively murmured, “Oh.”

Then, almost as if deliberately adding intentional punishment, Merlene held up the mirror, and I morosely said, “Oh.” I thought, Please. No. Let me wake up or die. Please. It was like vainly attempting to look away from a train wreck. Only I was on the train.

Growing up, I possessed a weird tic. I would laugh at the most inappropriate times. If someone told me his or her mother had died, I would stifle an insane urge to guffaw. There was no way to politely say I would rather have had my eyelids stapled to a railroad track than look in that mirror. So I froze. The next thing I knew, I was laughing.

I looked as if Patsy Cline and Lady Bird Johnson had given birth to a poodle, only my bouffant was way more poofed up and solid. It was hard, remarkably stiff. If I had been Samson, the entire trajectory of history would have been altered; Delilah would never have been capable of shearing that monolithic concrete from my head. If I raised my eyebrows, my whole scalp migrated backward. I was a guy—in junior high school!

Somehow, in my near hysteria, I mumbled, “Thank you,” which came out sounding vaguely like a question. I slinked out the door, almost crawling, praying that no friend—actually, no other human—would see me before I got to the car. When Mom got in, I dove into the floorboard and began trying to flatten my hair down with my hands and spit. But it was like scraping a concrete yard gnome. I think my fingertips bled.

Mom yelled at me to leave it alone. “You need to keep it just like that till tomorrow, so Merlene can see it at church.”

There was about as much chance of that happening as hell getting a Baskin-Robbins. I figured I could leave it alone until the second we got home, and then I could drown myself in the shower with a jackhammer.

Again, however, the car wasn’t going toward home. We were heading down Race Street. It wasn’t until we pulled into J. R.’s service station on the town square that I remembered my little brother. Mom, frustrated at me for futilely attempting to get the mutant off my head, said, “Go in, and get Andy.”

I hope you’re getting the emotional picture here. I was fifteen years old and about to enter high school in a town of about ten thousand people, where everyone knew everyone, and I looked as if Merlene had dipped my head in Aqua Net and dragged me through a donkey barn. And up until this experience I thought zits were the most evil scourge of the Devil. I said, “I am not walking into that gas station. It’s not happening. You can pull out a couple of hairs from my head right now and stab me in the heart with them if you want. I’m not going in there.”

“Timothy Eldridge, get out of this car this minute, and go get your brother.”

She’d used my first and middle names, so I knew the battle was over. I prayed that a freak tsunami would splash through Arkansas, washing away the entire town, including my hair.

I walked toward the firing squad, which was actually a glass door. I pushed it open to see three gas station attendants wiping tears from their eyes, looking toward the opposite corner of the room. I glanced over and saw Andy in the farthest chair, curled up in a ball, with exactly the same bouffant as mine. Every greasy gas station attendant in the lobby turned and saw me. One of the good ole boys snorted and said, “How can I help you, Miss Sinatra?” The hilarity started all over again.

Andy and I tried to beat each other to the car. I jumped in first and stammered, “Okay, let me get this straight. You actually allowed this hairdo thing to happen twice?”

“Oh, well, now, it doesn’t look that bad. It’s just …” She trailed off with a heavy sigh.

The remainder of the ride home, Andy and I avoided eye contact. It would only have ruined the false hope that we didn’t have the same alien on our head. Andy would have burst into tears, and I would have burst into uncontrollable laughter.

Mom barely had the car parked before Andy and I raced into the house and stood in our respective showers for about forty-five minutes. Although I’m sure Mom only took us to Merlene’s little shop of horrors, torture, and humiliation out of convenience, no boy from our family ever stepped foot in that place again.

The only consolation I felt from the experience was at church the following morning, when I marched in and watched Merlene’s look of shock. There might have been a snarl on her face, as if I’d deliberately defaced a masterpiece. I might as well have drawn nose hairs on the Mona Lisa with a Marks-A-Lot or taken a chisel to the statue of David. At any rate, fortunately, right about then, the old tic set in again, and I burst into peals of hysterical laughter.

We all have specific moments in our lives that define us. If you ever wondered why it doesn’t faze me for a single second that my forehead recedes to the back of my neck, now you know.

The Rock God Builds

Ginger Rogers DeMaris has been my sister’s best friend since they were in the second grade. For as long as I can remember, she has been part of our family. There has never been an event, joy, or grief in which G has not played an integral part. I proudly introduce her as my sister because she is, in every respect, one of us.

G makes cakes and beautifully unique centerpieces for anyone in our family getting married. She makes some of the best cookies I’ve ever eaten.

One thing that sets G apart from many of our friends and family is that she possesses minimal filter. She is loud and has never shied away from voicing her opinion.

I know if I’m ever in need, she’ll be there as quickly and surely as my other siblings. She loves Jesus. He has become fundamental to her in the past few years. I love it when she calls me with a question about the Bible. Because we were raised in the same church, she questions many things we grew up believing.

So she calls and asks—and I’d better have a sound biblical response. Breaking away from some aspects of what we’ve believed all our lives is hard. It’s scary. Ofttimes, when we’re talking, I’ll offer a response that categorically differs from our first beliefs. If G feels she’s standing at the edge of a cliff, staring down into blackness, hearing the Lord yell, “Jump! I’ll catch you!” she still asks, “Are you sure?”

I love saying, “Yes, I’m sure.”

Trust me, G’s questions always compel me to be sure. Many times, I have to say, “Let me get back to you on that one.” Then I study before telling her what I believe scripture teaches. It’s a good balance. It’s that iron-sharpens-iron thing.

One of G’s sons is working through his belief in God’s presence, not just in his life but also in the world. He questions whether God cares enough about us to intervene in our lives or even if God has the power to help us at all.

G called me one day with the age-old question that all students of philosophy ask when they want to stymie their opponent. She hit me with a question from her son: “If God is all-powerful, if he is omnipotent, could he make a rock he couldn’t lift?”

Surprised, since I hadn’t heard that question in eons, I figured it was like an internet hoax that keeps resurfacing and just won’t die. I said, “Yes, he can. And drugged travelers wake up to find themselves in motel bathtubs filled with ice and a kidney missing.”

I told G that he’s asking the wrong questions, and I have two responses.

First, everything God does has a purpose. Everything has a plan and serves a God-given reason down to the smallest, most seemingly insignificant speck in the universe.

Proverbs 16:4 (MSG) says, “God made everything with a place and purpose,” and Ecclesiastes 3 tells us emphatically that there is a time for everything, and God is in control of it all. We can choose joy and peace in the midst of life’s adventure. God gives the faith we need to make it through.

The bottom line here is that G’s boy is asking the wrong question. The question is not “Could God create a stone he couldn’t lift?” The question is “Would God create a stone he couldn’t lift?”

Why would he? What would be the purpose? It would be counter to his very nature. And if nothing else, God will always be true to his nature. Being inconsistent in his nature is probably the one thing he can’t do. Malachi 3:6 (NIV) says, “For I the Lord do not change.” Numbers 23:19 (ESV) says, “God is not man, that He should lie, or a son of man, that He should change His mind. Has He said, and will not do it? Or has He spoken, and will He not fulfill it?”

The good news is that God can create a stone as big as he likes. And the even better news? God can lift any stone he chooses to pick up.

Here’s the second part of my response: it seems to me that we mortals are the only ones who create stones we can’t pick up. We build skyscrapers, sculpt statues, and erect monuments, great architectural masterpieces we will never be able to lift with our own hands by our own strength.

And it is we mortals who have built stones the Lord can’t lift.

We have, all humans, picked up stones that seem small and easy to lift, believing we can move them anytime we choose, only to find them far too heavy to free ourselves from. Over time, without our even being fully conscious of it, we can no longer lift them. Resentment, bitterness, anger, drugs or alcohol, fear, shame, pride and self-righteousness, doubt, stress and anxiety, depression, codependency, buried wounds from childhood, hate, envy, dependence on religiosity and haughty principles—the list goes on.

These are just a few of the stones the Lord can’t lift—not until we ask him to. Until we realize the futility of our attempts at moving them. Until we find ourselves buried underneath them, unable to breathe.

I believe that more often than not, people find life more manageable if they can blame-place God for all their problems. They can attempt to minimize his power by asking him to perform a miracle diametrically opposed to his nature, when in fact, this gracious Father is waiting just around the curve of the mountain to move it out of their lives.

That place where we find ourselves is what we recoverers call “rock bottom”: the moment we realize we are buried, crushed beneath the rubble of our sin, and are helpless to move or get out from under it. It’s the moment we realize our lives are out of control, and we have no option but to put pride aside and surrender to the only One who is able to lift the rock and move us into security. It’s a scary, humbling place to be. But the freedom, peace, hope, and expectancy we gain make it eternally easier to keep those pesky little rocks from returning.

It’s about having faith. The Lord even promises to provide us with the confidence we need to believe, even with legitimate questions to God, such as “Did you call it sand because it’s between the sea and the land?” or “How long did it take Jesus to be potty-trained?” or “What exactly were you thinking when you made the avocado pit so big?”

Personally, I almost think that last one is a valid question. I know God has a good reason for everything, but that colossal avocado pit is a waste of functional avocado space, in my opinion. Think how much more avocado there would be if the pit were the size of a mustard seed. Most people have never seen a mustard seed, so this lesson would be much easier if the scripture said, “If you just have faith the size of an avocado seed, you can say to that mountain, ‘Get on outa here,’ and it will be done.” Everyone would say, “Oh yeah. I get it.”

Or, in the context of our story, “How long must I wait for this rock to be lifted?” It’s all about asking the right question. We will, all of us, have rocks that need to be lifted at some point in our lives. Where will you find the strength to be rid of yours? Will you continue asking questions that need no answer? Or will you surrender your pride and will to the One who is waiting to move the mountains for you?

Is this not the fast that I have chosen: To loose the bonds of wickedness, to undo the heavy burdens, to let the oppressed go free, and that you break every yoke?

—Isaiah 58:8 KJV

Cast your burden on the Lord, and He shall sustain you; He shall never permit the righteous to be moved.

—Psalm 55:22 NKJV

For I, the Lord your God, will hold your right hand, saying to you, “Fear not, I will help you.”

—Isaiah 41:13 NIV

What God Looks Like

One of the colossal mysteries of life is the ease with which most humans find fault with themselves. I include myself in that number. It’s even easier for people to point out the frailties of others, maybe because it makes them feel better about themselves and their own weaknesses. In the economy of the world, we’ve lost track of what it means to outdo one another in showing honor.

I have been the recipient, on several occasions, of someone saying, “Oh, I was just kidding,” after delivering a hurtful, damaging statement, as if kidding heals the cut. Just for the record, so you’ll know, your children will know, and your children’s children to the fourth generation will know, “I’m just kidding” is always a lie. What if we deliberately chose to live by Romans 12:8 (ESV): “Be devoted to one another in love. Honor one another above yourselves”? Those words are simple yet profound. How often do we purposely take the time to tell others that we recognize a specific strength or gift that sets them apart from the rest of the world?

I’ve done this a few times lately, and I get fascinating responses: either they shut me down because they fear being vulnerable to encouragement or are surprised anyone would notice something good about them, or they are confounded and embarrassed because it’s much easier to believe the bad. After all, the bad far outweighs the good. I sometimes get the feeling they think I have some sort of untrustworthy agenda for encouraging them.